This is my mother holding my oldest brother just a couple of years after her beloved brother was killed in World War II.

They were close in age and friendship; they were each other's confidants. He was twenty-one, and she was nineteen at the time of his death.

Growing up, I heard countless stories about him, including what it was like for her the day she learned of his death.

However, being a kid, they were just ambiguous tales to me. But as an older adult, after watching my own children go through the traumatic death of a sibling, and the instant shattering of the family unit as a result--I can't imagine the excruciating pain she carried.

Not to mention, throughout those turbulent war years, young women her age were expected and mandated to work seven days a week in the factories that supported the war effort. They never got a day off.

In fact, she stayed with a girlfriend in Fort Wayne, who also worked at the factory, in order to be closer to work.

The day she learned that her brother had been killed, another brother drove into town to break the tragic news to her. The factory supervisor excused her for the rest of that day, so she could be with her family at home on the farm.

However, trauma informed therapy was not a thing back then. Grieving and traumatized families were only provided a small pamphlet from the Department of Defense.

A few years ago, I read that pamphlet. . .it was a brief "carry on as usual" message.

My mom said her parents were never the same after that day.

Unfortunately, she quietly buried and carried that unresolved trauma for the rest of her life.

My mom married my dad two years later.

Around that same time, her brother’s remains—which had been buried in Holland for two years—were exhumed and brought back to the states. My mom said it was as if he’d been killed all over again. The original wound was ripped wide open again.

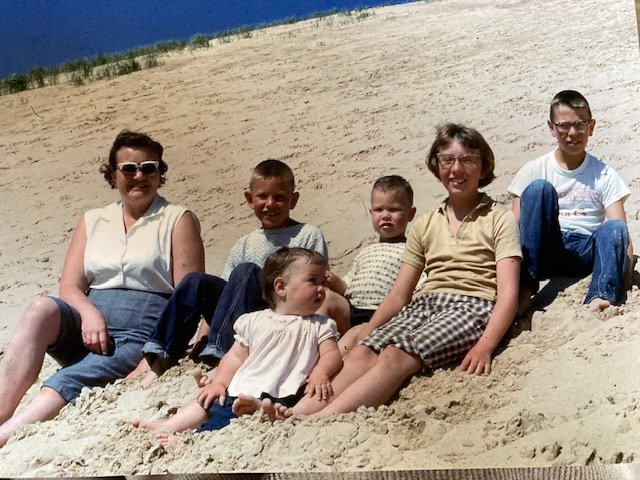

This is my mom holding me when I was a couple of months old.

My mother was a nurturing, selfless, and generous woman.

She faithfully helped my dad on the farm with planting/harvesting the field crops and gardening/canning the produce. She also lovingly raised five children, and even sewed many of our clothes.

Even though my parents worked hard on the farm, they also prioritized summer vacations in Northern Michigan. This was my first of many experiences on Sleeping Bear Dunes.

There was never a stranger my mom didn't extend hospitality to and nourish: visiting missionaries, local college students—even stranded motorists along the road due to a blizzard.

She also sat at the bedside of dying individuals; provided meals for grieving families; volunteered long hours in hot kitchens to prepare food for church camps and county fairs; gifted warm clothing to underprivileged children; and created a cozy and comfortable home for her children—and their eventual spouses and offspring.

Unfortunately, she got introduced to diet culture in midlife.

(Diet culture consists of ongoing scarcity mentality due to strict food rules, rituals, weighing scales, weight checking, food measurements, body size focus, body dissatisfaction, and the like.)

When I was six, she attended a weight loss group that met in the same church where my parents had exchanged vows twenty years earlier. It was conveniently located just around the corner from their farm.

At home, a weighing scale appeared on the linoleum floor at the top of the stairs leading to the cellar. It was an analog scale that revealed one’s weight with the pointing of an arrow. Weight charts were attached to the wall above that scale.

A smaller, spring-loaded plastic food scale sat on the kitchen counter. She placed every morsel of food on that scale in order to calculate a correct amount before eating it. Measuring cups also popped up at mealtimes.

Losing weight became her obsessive focus. . .which included weighing and charting me as well. (I wrote about it in my book, Starved to Obesity.)

For whatever reason, that church diet group either fizzled out—or she quit attending it.

Then, she saw a doctor in Fort Wayne who put her on another diet.

When that diet failed her, she started yet another one.

That food plan was printed on a large 11x17 sheet of paper folded into thirds. It was attached to the front door of the refrigerator with a magnet.

A Mason jar filled with a mixture of buttermilk, poppy seeds, and mustard sat on the top shelf of the refrigerator. She poured that yellow liquid over chopped iceberg lettuce--and no one was allowed to touch it.

Diet books began accumulating on the end table next to her glider rocker.

Then she joined another weight loss group. This one had weekly weigh-ins and points assigned to each food; which she meticulously kept track of each morsel. I remember there were colors assigned to them as well, and she obeyed the various rules for awhile.

After that diet, she committed to a medically supervised fasting program recommended by another doctor. That group met at the local hospital, and she lost a lot of weight one summer. . .but then gained it back a short time later.

If the Internet was a thing in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, she would’ve joined a weight loss challenge, detox. or boot camp. All three would’ve greatly appealed to her; plus, she wouldn’t have had the embarrassment of leaving home to attend the meetings.

Unbeknownst to anyone, she was suffering from an eating disorder that I saw glimpses of at various times throughout my childhood.

However, as a child, I didn’t have the language to articulate what I witnessed; I just knew she was sad, sick, and laid on the couch a lot.

It profoundly bothered me; my undeveloped brain couldn’t understand that her tears and aloof state of mind had nothing to do with me. I also couldn’t comprehend why she took a pair of scissors and cut herself out of a picture.

By the time I turned 17, I was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. However, in the 1970s, mental illness great stigma and shame attached to it. My parents swept the eating disorder under the rug and never mentioned it again—even though my emaciated condition was obvious.

My mom was suffering deep within and desperately needed compassionate help and care.

Not another diet.

And certainly not the embarrassment of another weight loss disappointment.

Even though her weight continued to significantly fluctuate, no doctor ever recognized she may have had an eating disorder. . . and no amount of weight-shaming and dieting was going to fix it.

Mom at age 79

Unfortunately, in her sixties, the cascading effects of chronic dieting caught up with her. She’d developed diabetes; followed by heart disease and eventually, several stents were placed throughout her body to open clogged arteries.

Everywhere she went, she carried a little cosmetic bag in her purse where she stored a glucometer, test strips, an insulin injection pen, and alcohol wipes. She’d prick her fingertip for a bead of blood—and then inject a meticulously calculated amount of insulin into her stomach.

One of my parent’s kitchen cupboards was devoted solely to diabetic supplies and pharmaceuticals for hypertension and high cholesterol. Another cupboard in the laundry room contained surplus diabetic supplies.

Mom routinely saw a cardiologist, nephrologist, endocrinologist, podiatrist, and family doctor.

Some years later, she suffered a couple of heart attacks and a debilitating stroke.

I was with her in the emergency triage room when she was actively stroking. She couldn’t move or speak; tears streamed down the sides of her face.

It was traumatic for her—and for me—as I helplessly watched the horror expressed in her eyes.

One of the last pictures of my parents. After the stroke, Mom lost eighty pounds and lived a couple more years.

She passed away at age ninety; and she remained a caring, loving, and selfless person to the end.

The quality of her life—for much of her adult life—had been hijacked by an eating disorder.

Her doctors were focused on her weight, blood work, tests, and pharmaceuticals.

They were well-versed in recommending diet and lifestyle changes.

Sadly, referrals to eating disorder specialists were never considered or recommended.

Even a generation later, I had the same experience with all of my physicians throughout the years—even though my medical charts revealed significant weight fluctuations.

Thankfully, my mother is now out of life’s suffering and pain; however, I can’t help but wonder how much differently her life would’ve been had she received trauma informed therapy and compassionate/skilled care for maladaptive eating behaviors.

Instead, she joined weight loss programs.

She is not to blame whatsoever.

She lived in an era when mental illness was associated with the insane asylum.

Today, we know so much more about the brain.

We know it can become injured by trauma, sick from disease, or changed by a life-altering event or mental illness. And, it has the capacity to heal if given the appropriate treatment and care.

And now we also know that eating disorders have biological, psychological, and social components to them that require specialized care. . .not weight loss challenges, boot camps, and detoxes. Thanks to skilled therapy and treatment, many people have fully recovered.

My mom did the best she could; in spite of her suffering.

She continued to embody a life of sacrificial love and care for others even until her final moments.

Some of her last words before falling into a deep sleep were, “I can’t worry about it anymore”—referring to having enough chairs for everyone to sit—as loved ones gathered around her bed in the intensive care unit.

After she passed, the lengthy line of folks who attended her visitation at the funeral home and packed the church for her funeral, attested to the powerful impact she had on the community.

She left a legacy of what she so desperately needed for herself: compassionate care.

The intense pressure of maintaining a very public weight loss “success story” persona affected me psychologically—and eventually triggered an eating disorder.

I didn’t even realize I had become trapped until more than a decade later, because it was such a subtle, downward spiral into captivity.

The scarcity mentality and body size obsession of diet culture has even infiltrated the health and wellness industry. I fell prey to it soon after I lost 100 pounds in my late 40s. It blindsided me without warning. However, I’m not the only one; others have privately shared their similar stories with me as well.

That's why I'm passionate about the course/workshop I’m creating: "How to Escape the Pitfalls of Diet Culture."

I’ll be taking a deep dive into it; sharing the nitty-gritty details of how I got blindsided—the insights and knowledge I’ve gained through lived experiences, and how I’ve escaped.

I’ll also provide the expert resources that helped me, and the practical steps that facilitated my eureka moment and resulting recovery.

It is possible to eat intuitively again. . . without falling prey to the scarcity mentality of diet culture: strict food rules and rituals, scale and measuring cup obsessions, and preoccupation with body size. . .all triggers that can fuel eating disorders for those with a propensity to them.

If you’ve been trapped by a food addiction and an eating disorder, you can escape both!

My passion for this topic is burning deep within me, because being trapped sucks the joy out of living.

I’m excited to invite you into the full disclosure of my story—especially from recent years—so that you may gain the insight and knowledge for your own journey to freedom.

Let me know if you want to be notified when it’s ready.

Freedom is possible!

Emily Boller, wife, mother, artist, and author is on a mission to create expressive works of art in her lifetime; and to bring awareness to the potentially harmful traps of diet-wellness culture.

In her free time, she loves to chase sunrises, grow flowers and vegetables, and can homemade soups.